Dakar court to give verdict on Monday on whether Hissène Habré is guilty of murder, torture, rape and crimes against humanity

This is a modal window.

More World news videos

-

Hundreds compete in race in Sweden’s swimrun season – video

-

Canada wildfires: South African firefighters break into song and dance as they arrive at Edmonton airport

-

Houses collapse during severe floods in southern Germany

-

Victims ‘hope for justice’ as former Chad dictator Hissène Habré awaits verdict

Chad’s former dictator is to learn his fate on Monday after a 26-year battle by his alleged victims to bring him to justice.

A court in Dakar will decide whether Hissène Habré is guilty of murder, torture, rape and crimes against humanity in the culmination of a five-month trial.

The landmark case is the first time the courts of one country have prosecuted the former leader of another for alleged human rights crimes. Activists say it gives hope to the victims of dictators that it is possible to bring their tormentors to justice.

Habré, hiding his face behind sunglasses and a voluminous white turban, sat in court each day to hear dozens of Chadians describe the horrors they suffered at the hands of his officials.

On one of the most dramatic days of the trial, a woman who had been imprisoned at the presidential palace revealed a secret she said she had been hiding for 30 years: she accused Habré of raping her four times.

Habré did not speak and stared straight ahead as she made the allegation, as he did throughout the trial except the first day, on which soldiers dragged the former desert warlord into the courtroom kicking and shouting insults, and pinned him down. Later, his legal team dismissed the woman, Khadija Zidane, as a “nymphomaniac prostitute”.

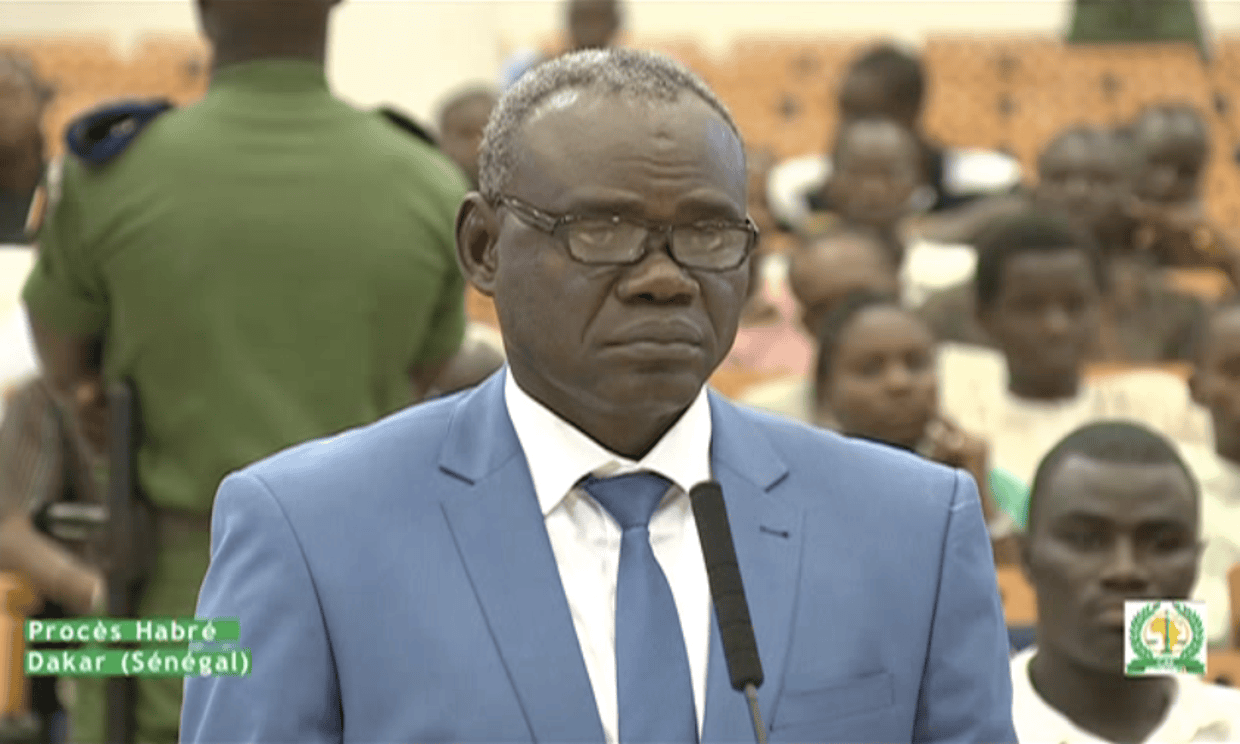

Habré’s alleged victims have pinned all their hopes on a conviction. Clément Abaifouta, who was a young student when he was arrested and imprisoned for four years, during which he became known as the “gravedigger” because he was forced to bury the bodies of his cellmates, said the experience had ruined his life.

This is a modal window.

“For my four years of detention, I did not exist. I was like a tiny coin, buried in a hole,” Abaifouta said. “For four years I went through terrible treatment, I slept on the floor. You get sick and you don’t get medicine. You just wait for death to come.

“This has marked my life. I was forced to bury people – my friends – who, maybe, if they had just had an aspirin or some other small treatment, would have survived. Men were taken out of prison only to be killed, and women to be raped. This was a nightmare for me. I was a victim of a system that has broken my life.

“When I hear people ask ‘what if Hissène Habré is not convicted?’, I can’t even think about it. Just put me in the fire and burn me now. I was out of my mind when I gave evidence – I could have jumped on him. I couldn’t stand that I was sitting one metre away from the person who did this to me, and he didn’t say a word. It was the worst insult. It was like he took all the victims, and just threw them away.”

Habré’s legal strategy was to not recognise the Extraordinary African Chambers, which was set up by the African Union and Senegal, the country to which he fled in 1990 when Chad’s current president, Idriss Déby, marched on the capital, Ndjamena, and overthrew his former ally. Before he left the country, Habré is accused of emptying its coffers, money that prosecutors hope can be clawed back and paid to his alleged victims.

The trial breaks new ground in Africa, where there has been growing resistance to the international criminal court’s perceived racism: all the investigations the latter has opened so far have been in African countries. Senegal’s method is being seen as an alternative, and a precedent-setter for the continent.

However, Reed Brody, a Human Rights Watch campaigner nicknamed the “dictator hunter” for his tenacity in pursuing both Habré and Chile’s Augusto Pinochet, thinks the greatest precedent is not a legal one but the message it sends to survivors of other regimes.

“What’s really precendential here is that survivors have fought to bring their dictator to justice. It serves as an inspiration for other victims,” he said.

Prisoners under Habré’s regime were allegedly forced into cells so cramped that they could not turn around; many suffocated to death in the 50-degree heat. Souleymane Guengueng, one of the leaders of the victims’ campaign, stopped breathing three times and nearly died: he considers it an act of God that he did not. He vowed that if he got out he would fight to bring his torturers to justice.

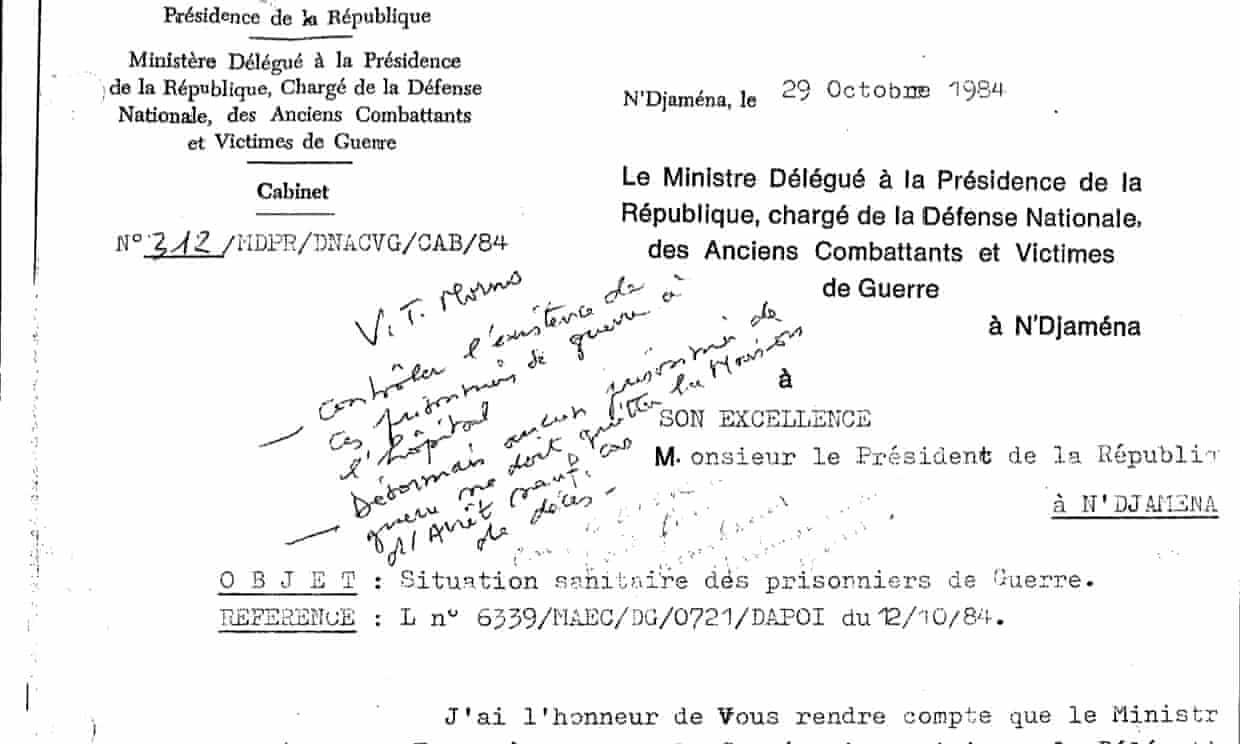

Guengueng’s meticulous documentation of survivors’ stories was key to the prosecution’s case, along with a huge tranche of documents that Brody found strewn in an old Chadian army building. The documents point to 1,208 people dying in detention and 12,321 victims of human rights violations, though in 1992 the Chadian Truth Commission put the death toll at 40,000.

Dapper in a black fedora adorned with bright feathers and a large silver crucifix around his neck, Guengueng, in Dakar to hear the verdict, took off his glasses to reveal damaged eyes, ringed with pale blue. He was locked up in pitch-dark solitary confinement for three months and almost went blind.

“All the suffering we went through in prison, the torture, the deprivation of food and healthcare, led me to wonder how someone could make people endure that – could treat them like animals,” he said. “In court, I was scared Habré would just explode – it was incredible for a human being to take in all the things we said about him and not crack. I will forgive him after justice, not before.”

For Abaifouta, the trial should serve as a warning to other tyrants, and though a conviction cannot mend his broken life, would nevertheless be a relief. “For a victim like me, it’s going to be one of the greatest days of my life,” he said. “For 26 years we have braved fear, violence and humiliation. It’s the climax of our struggle.”