Syria Watch

Syria Justice and Accountability Centre: Filling the Justice Vacuum in Syria

As a result of the relative calm following the US-Russia brokered ceasefire, widespread anti-regime protests have taken place throughout Syria for the first time in years. Syrians in Aleppo, Idlib, Homs, Hama, and parts of Damascus took to the streets to demand freedom, declaring that the revolution is still alive. Islamist groups Jabhat al-Nusra and Jaish al-Fatah, however, immediately disapproved and have intervened to disperse the protesters. The Islamist groups appear to have cracked down because the protesters were holding the “revolution flags” and signs calling for secularism and democracy. Activists reported that Islamist militants threatened them with death if they did not immediately leave the streets. The militants also smashed recording equipment and cameras, seized and tore apart revolutionary banners and flags, and detained some protesters.

After seizing neighborhoods and towns from either the government or opposition fighters, Islamist factions implemented so-called Sharia courts to mete out justice in the areas which they control. These courts have no written laws or legal texts to define procedures and punishments. A video taken from one of Jabhat al Nusra’s Sharia courts shows that judges do not adhere to a penal code, and instead, dole out punishments based on their own discretionary interpretation of Quranic law. A majority of these judges and clerks lack experience or academic qualifications in either civil or Islamic jurisprudence. As a result, the courts have often times been the scene of inconsistent, unfair, and vengeful trials.

These Sharia courts are also inconsistent in their interpretations of Islamic law, varying based on what school of Islam the faction follows. According to some Syrian activists, the courts interpret Sharia law to exert their own faction’s influence and goals, a problem akin to the justice system under Bashar al-Assad’s government. As a result, Syrians cannot use the courts to fairly address simple complaints, let alone human rights violations committed by the same factions that control the courts. Due to Syrians’ lack of access to fair dispute resolution mechanisms, a justice vacuum has emerged that Islamist militants have been unable to fill.

With no avenue for legal recourse, some Syrians have fought back. Recent footage from Marat al-Nuuman in Idlib show protesters chanting against Jabhat al-Nusra and tearing down the Islamist group’s black flags. The reemergence of protests against both the government and Islamist groups indicate that, despite five years of conflict, Syrians desire more than basic food and aid. It also signals a strong rejection by some segments of Syrian society of the hardline values and systems imposed by groups like al-Nusra.

A group of protesters tearing down an Al Nusra flag | Photo Credit: Hany Hilal (Facebook)

A fair and balanced legal system is one of the demands of the Syrian people. Such a legal system would adhere to the rule of law, abide by due process guarantees, grant fair trials, punishments, and redress to victims, and hold perpetrators accountable regardless of their affiliation. Syria’s judicial system is a long way from these international standards, which is why institutional reform is needed. The Sharia courts are not reform-minded. Instead they repeat the same failures of the current system and add additional chaos with conflicting and arbitrary rules. A key pillar of transitional justice, institutional reform, could include the vetting of judicial personnel, structural reforms, oversight, transforming legal frameworks, and education. Given their long history of abuse and corruption, the reform of Syrian state institutions will be vital to disabling the structures that allow abuses to occur, preventing the recurrence of violations, and instilling respect for human rights and the rule of law.

Syrian peace talks need to address the urgent need for institutional reform in Syria, particularly in the justice sector. These are issues that the negotiators cannot ignore and in which civil society can play a vital role, including by providing documentation of past institutional abuse. Additionally, international organizations and donors can support the reform process, both financially and through expertise that builds the capacity of local judges and lawyers.

While international experts largely focus on criminal accountability through international tribunals, the domestic system will also need the ability to address human rights abuses as well as ordinary complaints. International justice remains a priority, but without reform and capacity building of Syria’s justice sector, the same problems that led to dissatisfaction and conflict will inevitably continue, no matter which government emerges in the post-conflict period.

For more information and to provide feedback, please contact SJAC at info@syriaaccountability.org.

Syria Deeply Weekly Update: The Art of the Uprising Turned War in Syria

|

Mohammad Al Abdallah: Five Years on, We Must Focus on the Victims of Syria’s Atrocities

This was co-authored by Shabnam Mojtahedi.

As the conflict in Syria enters its sixth year, gross human rights violations remain one of the main features in the conflict. Although the anniversary of the uprising this year has coincided with a U.S.-Russia brokered ‘cessation of hostilities’ agreement that has, contrary to the expectations of many observers, lasted since Feb. 26, the big picture in Syria appears bleak.

The Syrian government forces and rebel armed groups have been committing gross human rights violations at an alarming scale, dragging the country into an endless cycle of violence and revenge attacks. Torture, in particular, has been one of the most widespread and well-documented acts of violence in the current conflict.

The practice of torture has a long history in Syria and was common during the three decades of former President Hafez al-Assad’s rule. Syrians shared thousands of accounts of torture and the mistreatment of political prisoners in detention. Several novels were written on the abuses in Tadmur Prison alone. No real changes were brought to the security forces, detention conditions, or even the justice sector after Bashar al-Assad, Hafez’s son, succeeded to power in Syria. The practice of torture continued – something I faced and witnessed myself during the few months I spent at Sednaya Military prison in 2006.

As the recent uprising of 2011 broke, security agencies, relying on decades of experience in arbitrary arrests, torture, and fear, became as ruthless as ever. Detention centers employed a revolving door arrest campaign, and the aim of torture shifted from the extraction of information to merely killing detainees. The scale of brutality shocked the world, particularly after Caesar, the now well-known military police photographer, defected and left Syria, displaying the photos of torture for all to see.

But how has the government’s increase in violence influenced Syrians in the opposition? Rather than fighting against the use of torture, certain rebel groups, including factions of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and Jabhat Al Nusra, quickly learned from Assad’s practices and began perpetrating horrifying acts of torture of their own. They introduced opposition-controlled secret detention centers, and stories and videos of their atrocities began appearing online.

For many Syrians, torture has become a daily part of life, whether from a broadcast on the news, videos on YouTube, or knowledge that a friend or relative experienced or died from the abuse; yet, the majority of Syrians are not mobilizing against the practice. Although this may be because Syrians inside the country fear for their safety, Syrians in the Diaspora have also turned a blind eye on such practices.

Through my work on Syria, I have interviewed hundreds of torture survivors over the course of a decade, witnessed torture first-hand at the Sednaya Military Prison, and most recently, have been leading the Syria Justice & Accountability Centre’s work on documentation. Over the years, I have been able to identify the following trends regarding torture in the Syrian context:

1. The practice of torture is increasing. At the beginning of the uprising, Assad and his forces used torture to suppress political dissent, but now almost all sides are implicated in the practice.

2. Torture is being justified. Sectarianism in both Syria and Iraq is growing. Sectarian hatreds are not only increasing the brutality of torture but also giving Syrians and Iraqis a reason to excuse the perpetrators — as long as the perpetrator belongs to their own sect. This is true even among educated Syrians.

3. Torture is no longer a private matter. Historically, torture in Syria has been committed in detention centers, away from the public eye. Sometimes videos were leaked, but overall it was the government’s dirty secret. In today’s Syria, torture has become a public act, thus normalizing its practice in the street, check points and on the fighting fronts. Onlookers can even cheer for the perpetrators, publicly showing support for its practice.

4. Torture is committed in groups. One of the most alarming trends is that torture is being committed by groups of perpetrators. The evil of a single perpetrator inflicting this type of harm on another human being is easier to comprehend than when it happens in a group. Rather than voicing an objection or a sign of empathy, they encourage each other, as if competing to see who the more brutal perpetrator is.

5. Syrians in the Diaspora are supporting torture. Often, I have seen Syrian refugees post torture videos and slogans calling for revenge on social media. Syrians in the Diaspora denounced the conviction of a former FSA fighter in Sweden after he posted a video of himself torturing a prisoner in Syria in 2012. Swedish investigators found the video, and a court sentenced him to five years in prison. Despite the clear evidence, many Syrians did not believe a punishment was warranted for “treating Assad soldiers the same way they treated us.”

6. Only justice will help deter torturers. Syrian human rights activists, lawyers, and ordinary people have worked tirelessly, and at extreme risk to their lives, to document the violations occurring in the conflict and to shame the perpetrators internationally. But, after five years, it is clear that documentation alone is not deterring the practice, or even opening a debate within Syrian society about the wrongness of torture. For documentation to be truly effective, it must be accompanied by accountability processes. Accountability can begin now through the jurisdictions of European and North American courts and should continue into the future.

The practice of torture threatens to further tear Syria’s social fabric and increase sectarianism. Syrians need to better understand that torture affects every community, regardless of ethnicity or religion. In the long run, torture will continue playing a destructive role in Syria, even after the conflict ends, unless Syrian society uniformly condemns it and works to reform current and future practices. Most importantly, the current talks in Geneva must prioritize justice and accountability for torture and other human rights abuses and include investigations into and a condemnation of torture in the final peace agreement.

Mohammad Al Abdallah is a Syrian human rights lawyer and activist. Former political prisoner in Syria for two prison terms. Currently, he is the Executive Director of the Syria Justice & Accountability Center.

Shabnam Mojtahedi, Legal and Strategy Analyst of the Syria Justice & Accountability Center contributed to this article.

Follow Mohammad Al Abdallah on Twitter: www.twitter.com/Mohammad_Syria

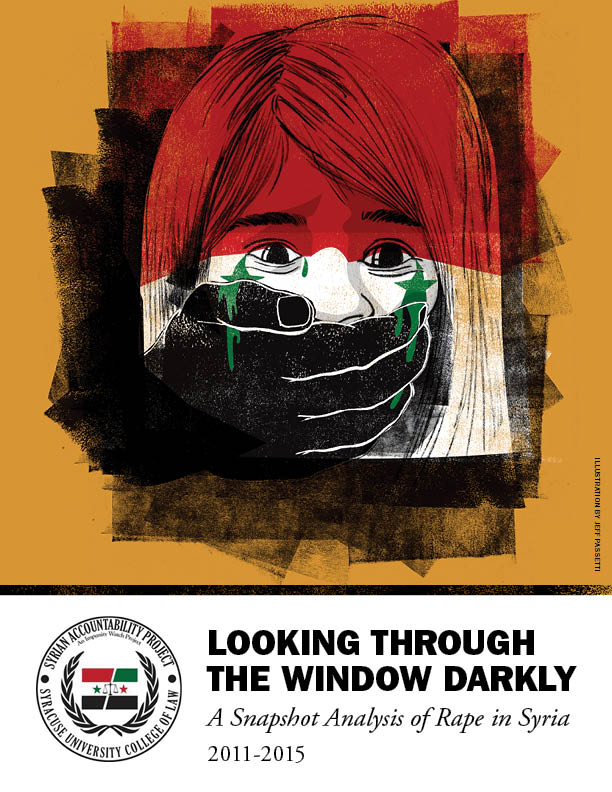

Syria Accountability Project: White Paper to be Released 24 March