Business Insider: Maps show how ethnic cleansing has become a weapon in Syria’s civil war

Between refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs), more than half of the Syrian population has left their homes since the war began in 2011. To understand why this has happened and what can be done to reverse it, one must examine the country’s demographics in detail.

A population shortfall

Syria currently has around 16 million residents — a far cry from the 2010 UN projection that the population would reach 22.6 million by the end of 2015. The birth deficit and excess mortality (violent and natural) have reduced the natural population growth by half since 2011. Even if refugees are added to the current population figure, the total would be only 21.3 million, or 1.3 million less than the prewar projection.

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has registered 4.2 million Syrians thus far, but that figure undervalues the actual number of refugees by at least 20%. Some refugees refuse to register for fear of being arrested and taken back to Syria (as is happening in Lebanon), while many wealthy refugees do not see the point of registering. So a more realistic estimate of total refugees is 5.3 million.

That number is expected to increase sharply.

In Aleppo province alone, escalating hostilities have spurred another 200,000 people to leave their homes in the past two months. The Russian offensive and the lack of short-term hope for peace have convinced many living in relatively calm areas to leave as well, and more may follow suit if the recent German-led plan to welcome more refugees is implemented.

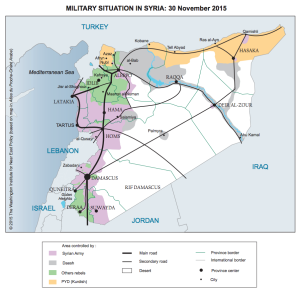

Areas of control

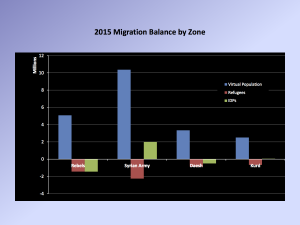

Although it is difficult to give an exact number for IDPs, the available data suggests that 6.5 million Syrians have fled violent areas for safer parts of the country. This includes about 2 million who have fled to the current government-controlled zone from areas controlled by other factions, as well as millions of others who fled one regime-controlled area for another due to intense fighting.

The areas held by rebels (the northwest, the south, and other small pockets such as Ghouta) have lost the most people because they are the least secure — Russian and regime airstrikes impede normal life there, and the presence of numerous different rebel factions creates persistent insecurity. The area held by the self-styled Islamic State (IS) seems safer, in part because it has a central authority.

Although religious minorities and secular Sunnis fled Raqqa and Deir al-Zour, they were replaced by foreign jihadists and Syrians displaced from Aleppo. In general, people tend to seek refuge where they have relatives, and where there is no fighting; the identity of the faction that controls the area does not necessarily matter to them as much.

The Kurdish area attracts displaced Kurds but few Arabs — no surprise given that the faction in control, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), aims to make the area ethnically homogeneous.

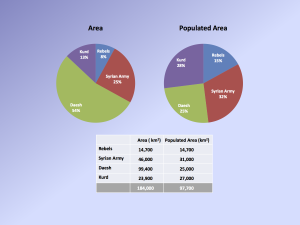

Mainstream media reports often highlight the fact that the Syrian army controls less than 17% of the country, and IS over 50%.

Yet these seemingly shocking figures do not factor in Syria’s geography — namely that 47% of the country is sparsely inhabited steppes. Of course, extending control over some of the steppes may hold strategic interest for IS; Palmyra is a traffic hub with important gas and oil resources, for example, and it borders Iraq and Jordan. In any case, the Assad regime controls the largest share of Syria’s residential areas, and also the most populated area.

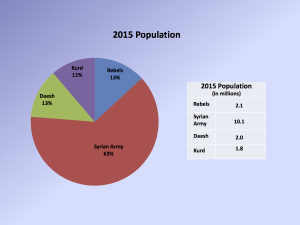

Around 10.1 million inhabitants live in the government zone, or 63% of the total resident population. The areas controlled by the other three main factions (Kurds, IS, and rebels) are roughly equal, with about 2 million each. In short, the regime has gone from controlling about 20 million Syrians prewar to about 10 million now.

Local ethnic cleansing

The large-scale population movements have not been a simple byproduct of war. Rather, they represent conscious strategies of ethnic cleansing by each faction.

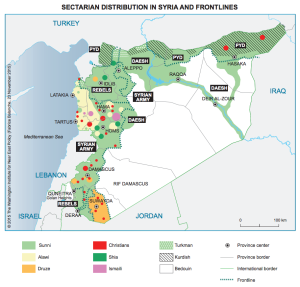

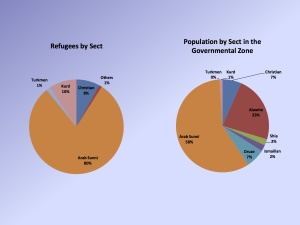

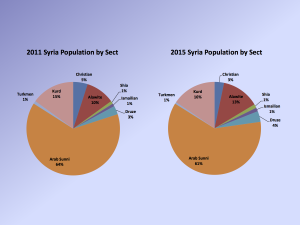

To be sure, the ethno-sectarian composition of the country as a whole has not changed much, despite the departure of disproportionately Christian and Sunni Arab refugees. Christians have traditionally been scattered throughout the country and do not have their own area of refuge like the Alawites and Druze, spurring many of them to flee abroad.

As for Sunni Arabs, because the insurgency took root in their ranks, they have been the first target of regime repression and airstrikes (though some Sunni clans support Bashar al-Assad and have remained safe in the government zone). Overall, Syria’s current population is 22% religious minorities, 16% Kurds, and 61% Sunni Arabs — in other words, not that different from the prewar composition.

These figures could change in the coming months, of course, particularly if the PYD creates a continuous zone of Kurdish control along the border with Turkey by seizing territories between Azaz and Jarabulus.

Any such move to connect the northwestern Kurdish enclave of Afrin with the rest of the PYD’s territory in the northeast (known as Rojava) could spur hundreds of thousands of Sunni Arabs to flee.

Meanwhile, expanded efforts to eliminate IS will likely produce an internal Sunni war between tribes supporting the terrorist group and other factions, creating further refugee flows.

For now, Syria’s overall population figures hide the rampant ethnic separation already occurring within territories controlled by each faction.

Acutely aware that its Alawite base is a shrinking minority, the regime has created a zone of control with 41% religious minorities, compared to the national figure of 22%. The army consistently prioritizes asserting its grip over Christian, Alawite, Druze, Ismaili, and Shiite localities.

In contrast, rebel victories often spur local religious and ethnic minorities to depart. Only the Druze area of Jabal al-Summaq in northwestern Idlib province remains in the rebel zone, enjoying special Saudi protection in connection with Lebanese Druze leader Walid Jumblatt — it is the fragile exception that proves the rule. Rebel groups dominate a Sunni Arab territory; the main minority there is Sunni Turkmen, which is probably the most anti-Assad group.

Similarly, all religious minorities tend to flee IS-held areas. Some Kurds have remained behind; IS does not seem to distinguish them from local Sunni Arabs, probably because they are Sunni believers as well. That said, many secular Kurds have fled to PYD territory.

In the Kurdish zone of Rojava, Arabs must agree to live as minorities — as the Kurds did during centuries under Arab rule — or leave. This reversal of power is intolerable for many Sunni Arabs accustomed to dominating the northeast, leading some to support IS.

The fact that the regime-controlled zone is the most diverse does not mean that Assad is more benevolent than the rebels, Kurds, or IS. Rather, it reflects his political strategy.

He knows he must expel millions of Sunni Arabs to make the balance of power more favorable to minorities who support him. He also needs to divide the Sunnis by redistributing land and housing that belonged to refugees, making loyalist Sunnis who remain behind even more beholden to him and pitting them against any who decide to return.

In sum, the Syrian conflict is a sectarian war, and ethnic cleansing is an integral part of the strategy used by various actors, even if they claim otherwise.

What ethnic cleansing means for Syria’s future

|

Thomson Reuters |

A man rides a bicycle near damaged buildings in Jobar, a suburb of Damascus, Syria

Although many refugees and IDPs will want to return home once peace is established, they will be unable to do so because of their ethnicity and/or political affiliation.

Resettling displaced people will become a strategic question for each player. Their efforts at local ethnic cleansing are already making Syria’s de facto partition more and more irremediable. Sectarian diversity is disappearing in many areas of the country, and this process of regional homogenization is drawing internal borders.

Yet formal partition is not necessarily a good solution. It could generate new conflicts, as seen when Sudan split and then the new country of South Sudan dissolved into civil war.

Therefore, the international community may need to work toward a Syrian agreement that lies somewhere between the Taif Accord, which imposed a kind of unity on Lebanon, and the Dayton Agreement, which imposed a difficult partition on Bosnia under intense foreign supervision. Syria’s various communities will accept living in a new, united Syrian Republic, but not the Syrian Arab Republic as it existed prewar.

A federal system would be the best political regime because the previous centralization cannot be reestablished, whatever the ruling group.

Fabrice Balanche, an associate professor and research director at the University of Lyon 2, is a visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.

Read the original article on The Washington Institute For Near East Policy. Copyright 2015. Follow The Washington Institute For Near East Policy on Twitter.

SNHR: More Than 3173 Barrel Bombs Dropped On Syria since the Russian Military Intervention

Ecuador Ends Presidential Term Limits

By Kaitlyn Degnan

Impunity Watch Reporter, South America

QUITO, Ecuador — Ecuador’s National Assembly has passed a constitutional reform to do away with presidential term limits. The move faced widespread criticism throughout the country, especially from members of the opposition. The move is the latest in a pattern of Latin American leaders abolishing term limits – which started with Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. More recently, Nicaragua has constitutionally abolished term limits, while Bolivia is currently considering it.

The Opposition views the move as a threat to democracy because incumbent presidential candidates typically have an easy time getting re-elected. In Quito, protesters gathered outside the National Assembly building. Armed with sticks and rocks, they blocked major intersections with burning tires.

Correra announced that he would not be running for re-election when his term expires in 2017 on November 18, just hours before his party announced that it would back constitutional reforms to eliminate term limits. Correra’s current term will expire in 2017.

At the last minute, lawmakers added language holding off the implementation of the reform until May 24, 2017 – after the next president of Ecuador will be selected. The effect of the modification is that Correra will not be able to run for reelection as the term limits will still be in place at that time.

However, it is thought that after taking a “break,” Correra will most likely run for election again in 2021, at such time he will be able to continuously seek re-election following the expiration of that term.

Analysts have called his decision to step back for a term a “shrewd political move” – as Ecuador currently faces a number of economic issues. Ecuador has had to cut back on spending and increase taxes in recent months due to a fall in oil prices.

Other constitutional measures passed during the vote included the declaration of communications as a public service, the removal of collective bargaining for public employees, and putting the military in charge of domestic security.

For more information, please see:

Daily Mail – Ecuador lawmakers vote to end presidential term limit – 3 December 2015

Herald-Whig – Protesters clash with Ecuador cops ahead of term limit vote – 3 December 2015

New York Times – Ecuador Lawmakers Vote to End Presidential Term Limit – 3 December 2015

TeleSur – Constitutional Amendments Approved in Ecuador – 3 December 2015

TeleSur – Ecuador’s Opposition Responds with Violence – 3 December 2015

TeleSur – UPDATE: Ecuador Lawmakers Debate Constitutional Reforms – 3 December 2015

Malaysia’s National Security Bill Draws Criticism as “Tool of Repression”

By Christine Khamis

Impunity Watch Reporter, Asia

KUALA LUMPUR –

Malaysia’s House of Representatives passed a bill on Thursday establishing a National Security Council, which will have the authority to make decisions on all matters pertaining to national security. The National Security Council will have few limitations when responding to known or potential security threats. Human rights organizations and other critics have condemned the passage of the bill, saying that it will be used as a tool to abuse human rights by the Malaysian government.

Malaysia’s House of Representatives tabled the bill on December 1, but then passed it on Thursday with a vote of 107 in favor and 77 against. Those in Malaysia’s ruling party, Barisan Nasional, were strongly in favor of the bill.

Malaysia’s Prime Minister, Najib Razak has stated that the law is necessary for responding to extremism and terrorist threats in Malaysia. Under the law, Mr. Najib has the power to declare any area of Malaysia as a “security area” for up to 6 months if the National Security Council finds that the area is under a serious threat that could be harmful to the public and any national interest.

A Director of Operations of the Council will be allowed to prevent anyone from entering such areas, remove anyone from those areas, and to establish curfews and take possession of any property necessary to further national security. The Director of Operations will have the right to conduct searches and arrest people without warrants.

The members of a security team, which the Director of Operations will oversee, will be allowed to use any force necessary and reasonable to protect national security. Additionally, members of the security team will be immune from liability for any actions taken in good faith.

The National Security Council will be headed by Mr. Najib. Additional members will include Malaysia’s Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Defense, Minister of Home Affairs, Minister of Home Affairs, Minister of Communication and Multimedia, Chief Secretary, Commander of the Armed Forces, and Inspector-General of Police.

Human Rights Watch’s Deputy Director for Asia, Phil Robertson, has released a statement referring to the bill as a tool of repression, saying there is a “real risk of abuse” of the law. Human Rights Watch also has stated that there is already a wide range of abusive laws being implemented by Mr. Rajib’s government to arrest dissidents.

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) issued a press release on Thursday stating that the bill makes it clear that Malaysia’s government needs to establish reforms in their lawmaking process. ICJ’s Senior International Legal Adviser for Southeast Asia, Emerylynne Gil, stated that there seems to be “a disturbing pattern of avoiding deliberate care on legislation” on security concerns that also greatly implicate human rights.

The National Security Council bill comes amidst an increasing level of civil rights abuses and crackdowns on government critics.

For more information, please see:

BBC – Rights Group Condemns Proposed Malaysia Security Bill – 3 December 2015

International Commission of Jurists – Malaysia: the ICJ Condemns Passage of National Security Council Bill, Urges Reform in Lawmaking – 3 December 2015

The New York Times – Malaysian Security Bill Invites Government Abuses, Rights Groups Say – 3 December 2015

World Bulletin News – Human Rights Watch Claims Law Provides Expansive Powers That Could Fundamentally Threaten Human Rights and Democratic Rule – 3 December 2015