Kenya continues to deal with the repercussions of violence stemming from its disputed 2007 presidential elections, when political protests and targeted ethnic violence rocked the country, leaving thousands dead and hundreds of thousands displaced. For insights and analysis about how the country is dealing with the legacy of this violence through transitional justice efforts, we talk with the Head of our Kenya office, Chris Gitari, a Kenyan lawyer and transitional justice expert.

Below, Gitari explains how the country has responded to the crisis through truth-seeking and accountability measures, and how ICTJ is assisting civil society and government actors who are leading these efforts. He reflects on the impact of Kenya’s Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission, the challenge of reforming the practices of Kenya’s police forces, and explains how Kenyans are reacting to the ongoing cases against senior members of Kenya’s political leadership at the International Criminal Court, including current President Uhuru Kenyatta.

How would you describe transitional justice efforts taking place in Kenya today, and what is ICTJ’s role?

As a result of Kenya’s post-election violence in 2007-2008, we had a national reconciliation process—led by Kofi Annan—which aimed to figure out the root causes of the crisis, and how best to address them in short and long term measures.

ICTJ first began our work in Kenya in 2008, and since then we have supported these processes, in particular those of justice and accountability, as well as truth and reconciliation. Our aim is to ensure the vindication of victim’s rights, especially those who suffered serious violations in the post-election violence. We try to seek some redress for them and also the reform of institutions so that there cannot be a “next time” i.e. guaranteeing non-repetition. These are the main goals for ICTJ’s work in Kenya.

I think ICTJ’s role in Kenya has been to de-mystifying transitional justice as a process and approach, and to explain technical concepts of reparations and supporting domestic accountability measures.

Kenyans, as well as the international community, have been closely following the investigations and prosecution of senior political figures in Kenya by the International Criminal Court, including current President Uhuru Kenyatta. The cases have been increasingly fraught with political interference and controversy, and the Kenyan government has continuously voiced its belief that those pursued for crimes during the electoral crisis by the ICC should be tried in Kenya, not at the ICC. Could you describe current public perceptions of the efforts to achieve some criminal accountability in the country? How well-equipped is Kenya to handle their own prosecutions for serious crimes in national courts, and what is ICTJ doing in relation to these issues?

For many Kenyans, the perception here is that the ICC cases have now turned into a sham and a farce. Kenyans do not know how the cases ended up being so weak. What we tend to see now is a blame game: you have people saying these cases have been politically undermined by the State, and there is evidence to that extent. And now what we are seeing is the possible slow-motion collapse of these cases. This is probably not only due to the lack of investigations by the former prosecutor, but also due to witness tampering and interference with evidence.

There is a widespread perception that the state continues to have a hand in undermining prosecutions; this in turn generates mistrust on any discussions on domestic trials. For example, this can be seen through attempts to set up special tribunals through legislation, all of which were voted down by the national assembly. Even when it comes to the investigation of these crimes, you find that there is complete disinterest, by both the Inspector General of police and the director of public prosecutions. All of this leads to the sense that there is an informal policy not to prosecute serious crimes.

For some time, ICTJ has supported an understanding of the role of the ICC among local actors including policy makers. We have worked to help them engage with the ICC more effectively—in particular the victims, who have a large interest in the ICC process. We have specifically worked with policy actors to support the establishment of domestic mechanisms, when they have been proposed.

When a Special Tribunal for Kenya was proposed, we undertook extensive analysis that indicated minimum requirements that such a mechanism should be required to meet. We also held forums with policy makers and civil society organizations to facilitate an understanding of how such mechanism would ideally work, and to build common ground.

There has been discussion of an establishment of an International Crimes Division of the High Court, which would deal with those most responsible for the post-election violence. We have worked with policy makers to help assess the proposal for potential weaknesses, but also identify opportunities with civil society actors; in this way, we are facilitating discussion towards common ground around this particular mechanism and the demand for criminal accountability.

We continue to work with the Judicial Service Commission, which is a clearing house for discussions on the International Crimes Division. These discussions are on-going, despite the fact that the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Inspector General of Police have demonstrated unwillingness to pursue post-election violence cases in terms of investigations and prosecutions.

Currently, we are analyzing proposals around the use of coroner inquests to pursue criminal accountability for persons who have lost their lives in certain situations—untimely deaths, unexplained deaths, and forced disappearances and people killed during the violence. For these and other crimes, there has been no accountability.

Kenya’s Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) was a major effort to establish the truth about past violations, whose mandate extends back to cover decades when other serious abuses occurred, involving issues such as corruption, displacement and dispossession of land. How successful was the TJRC, and how has its final report made an impact? In what way has ICTJ engaged with the TJRC?

The TJRC has had a very limited measure of success. This is because of the crisis around its Chair, the crisis around funding, and the crisis around its legitimacy in the political context. As a result, its report has not had the impact we would have wanted.

This does not mean, however, that the process was not important or that there aren’t efforts to do something with the report. Right now, together with others, we are engaged with the Department of National Cohesion in the Office of the President, the office of the Attorney General, the Interagency Committee on the implementation of the TJRC Report in trying to define a way forward for the implementation of the recommendations of the TJRC, given the very limiting political context— remember, we have a deputy president who has been named in this report, as well as members of parliament. Despite these difficulties, there is willingness to discuss aspects of the report and recommendations that can be implemented, without being antagonistic to the political leadership.

We have engaged with the TJRC process from the very beginning, including giving advice during the crafting of the legislation. We gave input but that input was not seriously considered, giving rise to some of the problems we saw throughout the operations of the TJRC and continue seeing now.

Despite these shortcomings, when the TJRC came into being, ICTJ provided a range of support: we were involved in setting up the database for victims, drafting the reparations framework chapter and also supporting the hearings on children and the chapter on Children and Gross Human Rights Violations. We directly supported their staff to fulfill parts of the mandate.

Now, we are providing advice on the kind of implementation framework that can work best for the country. Our approach is to see Implementation as an incremental process, meaning that we will focus on issues that can be dealt with now, issues on which the State is open and willing to engage. For example, we will be dealing closely with the implementation of reparations, but not forget the much more difficult aspects of the report, such as the historical lack of justice and criminal accountability. So it’s a long term process. We will focus on reparations because that is what is possible now, but won’t forget these other issues in the future when they become possible to pursue. We will also lend our expertise if victims groups decide to adopt new strategies that are non-State led, like private prosecutions.

What kind of reparations do victims in Kenya seek, and how is ICTJ working to support this effort?

The TJRC recommended various forms of reparations, which were based on a categorization of victims. Priority victims were the most vulnerable group, and they were flagged by certain criteria: victims who had suffered very serious violations or lost their loved ones or lost their lives. These victims are either children of other people or who have serious health concerns, or are in single-guardian households, or are orphans; these are victims who have suffered and are extremely vulnerable. This group would receive reparations in the form of rehabilitation and compensation.

Then the TJRC identified a second priority group, victims who suffered as a community, and who would be awarded collective reparations. These were usually victims who were marginalized in the community, or lost land as a community, and therefore had suffered very serious socio-economic injustices or were seriously marginalized. Here it the recommendations were about redressing the issue of land, giving them formal recognition, and essentially enacting beneficiary schemes.

Lastly, and most generally, you have national reparations to Kenyans, a broad type of reparation which is symbolic. The reparations to be given to this group are very broad, and include public apologies and memorialization or monuments to commemorate the victims, particularly of massacres and political assassinations.

For these categories of reparations laid out by the TJRC, ICTJ is doing what we can to support an engagement and discussion of these issues, as we encourage the State to bring together local actors to have this discussion.

Part of the effort to address the role of security forces during the worst of the violence has involved the reform of aspects of this sector. What is ICTJ’s role in the National Police Service Commission’s vetting process? What might we expect from its outcome?

The main objective of engaging the security sector is to support police reform efforts as they are the greatest human rights violators of in Kenya. As such, interventions around theNational Police Service are a key focus of our work.

The official police vetting process, which began in November of 2013, seeks to remove officers who are deemed unsuitable to serve due to their involvement with human rights violations, corruption, or other types of misdeeds. The goal is to ensure that when the process is done, the police are accountable, transparent, and efficient, and also that public confidence in the police is restored.

ICTJ has facilitated engagement between civil society and the National Police Service Commission in an effort to ensure full accountability during this process through public engagement. We have also supported the Commission by helping to set up the legislative framework for the vetting process, establish regulations, and basically doing general monitoring and feedback to the Commission on the ongoing vetting process.

A main priority of ours has been public involvement: currently we are supporting the Commission in its reframing of the vetting process so as to allow for increased public engagement. In the coming months, that’s going to be the key object of our intervention.

The post-election violence in Kenya was in many ways marked by sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Women who suffered this kind of abuse have few avenues to seek redress, and have yet to see their attackers faces justice. What kind of commitment, if any, have Kenyan authorities made to address the extent of SGBV during the conflict, and how has ICTJ been engaged?

It’s very clear that women were indiscriminately attacked, and bore the greatest proportion of sexual violence during the post-election crisis. What you can see is that in almost every incident where there were serious human rights violations, sexual violence was a key part of those violations: during the massacres, forced displacement of communities, during the police operations that took place—sexual violence was never far away. In nearly every type of event the TJRC analyzed, women were targets, and suffered disproportionately.

The official response to these experiences tends to be one of denial, or else is extremely weak. All of this has been exacerbated due to norms in Kenyan society, which is very closed when it comes to these matters. Even the TJRC notes that the only way it could get women to relay their experiences before the commission was by holding women-only hearings. What has made these issues come to fore has been the commission’s efforts to dedicate time and space in their reports to these issues.

In the context of the police vetting process, we have urged the police vetting commission that they must pay attention to sexual violence violations, for example, in how police have responded to complaints made to them about the actions of a civilian. Not only have we brought this to the commission’s attention, but we also held sessions to sensitize members of the National Gender Equality Coalition on gender-based violence, not only in terms of awareness about the police vetting process itself, but also in order to support efforts to bring victims’ complaints against police officers.

This has been one of the key values of ICTJ in the vetting process: very few organizations are able to connect these two aspects, police vetting and gender justice. ICTJ has been able to leverage its expertise to the benefit of the commission and the victims of sexual and gender based violence.

Kenya has a vibrant youth culture, and its members have grown up alongside sharp political and ethnic divides. How is the country working to address how children and young people experienced the violence of 2007-2008? Are youth groups engaged in efforts to address the past?

The youth in particular are very aware about the political divides—some of them have actually fallen prey to that. On social media, for example, you find very ethnically-biased discussion, and sharp rhetoric around ethnic lines, mostly by very young people. I can see these biases being transmitted to children and youth by the older generation. This is very worrying.

There must be concerted efforts to ensure young people are aware of the causes of the violations and the violence, including historical violations. But also, it’s critical to engage them in a constructive process that helps build the nation—not tear it apart. The youth culture in Kenya is a very vibrant one, and a lot must be done to focus on them.

The TJRC had aimed to have a version of their final report that was designed especially for youth, and it made efforts to hold hearings for children and youth. ICTJ’s Children and Youth program was very involved during the TJRC process and actively pushed for the drafting of a children and youth version of the TJRC report. Unfortunately, this was never produced, so instead, ICTJ and our partners, including UNICEF and GIZ, decided to develop a children and youth report. This report will focus on the experiences of young people, those who are the most volatile and easily mobilized to perpetrate violence. They are also usually victims of serious abuses, and as such, it’s imperative for them to be engaged in efforts to reconstruct the nation—there’s a lot of space for them to become engaged.

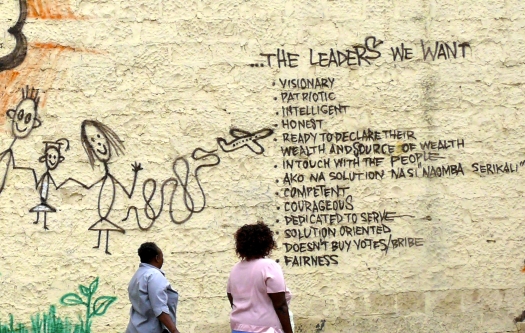

Photos: Police charge at protesters along the streets of Nairobi filled with tear gas (DEMOSH/Flickr); People watch on TV Kenya’s president Uhuru Kenyatta appearing in the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague to appeal for the crimes against humanity case against him to be dropped for lack of evidence, on October 8, 2014, in Nairobi. (SIMON MAINA/AFP/Getty Images); Voter casting his vote at a polling station (DEMOSH/Flickr); Political street graffiti in Kenya (Flickr); Police on the streets during election violence, January 2008 (DAUDI WERE/Flickr); Members of a youth corps campaigning for peace at the sprawling Kibera slum in Nairobi perform an act on July 28, 2014 reminiscent of deadly ethnic violence, following the disputed results of the 2007 general elections (TONY KARUMBA/AFP/Getty Images); Boys play on July 28, 2014 in front of a mural that calls for youth to live in peace in swahili language at the sprawling Kibera slum, in Nairobi, a hotspot of deadly ethnic violence following the disputed results of the 2007 general elections (TONY KARUMBA/AFP/Getty Images).