By: Adam King

Impunity Rights News Reporter, Africa

DADOMA, Tanzania — A new UN convention on the trade and use of mercury held its inaugural meeting on September 24, 2017 in Geneva, Switzerland. The treaty, known as the Minamata Convention on Mercury, seeks to cover a wide range of areas related to mercury,

“The treaty holds critical obligations for all 74 State Parties to ban new primary mercury mines while phasing out existing ones and also includes a ban on many common products and processes using mercury, measures to control releases, and a requirement for national plans to reduce mercury in artisanal and small-scale gold mining. In addition, it seeks to reduce trade, promote sound storage of mercury and its disposal, address contaminated sites and reduce exposure from this dangerous neurotoxin.”

The name of the convention is derived from a fishing town in Japan that involved many cases of mercury poisoning. The connection between mercury and African countries is its use in a process used to mine for gold.

Tanzania, Zimbabwe and Mali are but a few African countries that use mercury to separate gold from ore. The mining process that utilizes this method is known as artisanal and small-scale gold mining or ASGM. This process is utilized in rural areas where gold mines are located, but are not central mining hubs. While the process is not as intensive as opposed to larger mining operations, the practice does pose some health risks.

The danger of using mercury in ASGM have short and long term effects on those who come into direct contact with the mercury, “Mercury is a shiny liquid metal that attacks the nervous system. Exposure can result in life-long disability, and is particularly harmful to children. In higher doses, mercury can kill.” Children are often utilized in ASGM, given the relative ease of the process. For some, it is a way for them to earn money to support their families. The reliance on ASGM in rural communities has grown steadily over the years.

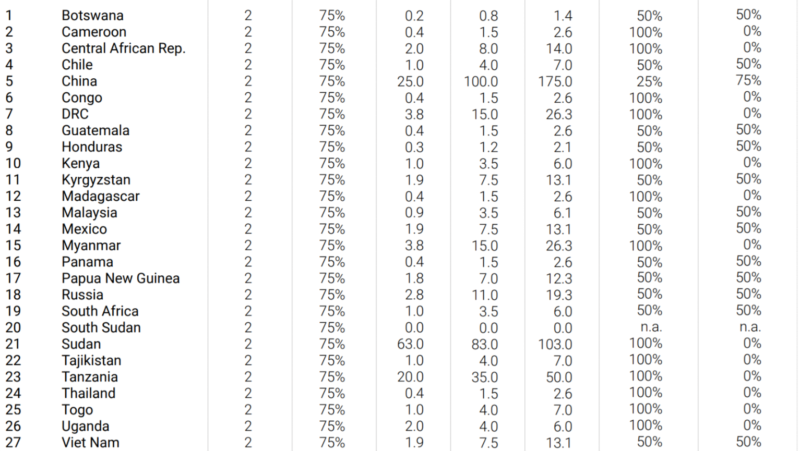

A report released by UN Environment details the amount of reliance on ASGM in Africa and worldwide,“ASGM is now responsible for around 20 per cent (600-650 tonnes per annum) of the world’s primary (mined) gold production. It directly involves an estimated 10-15 million miners, including some 4.5 million women and 1 million children.” While 20% seems to be a small percentage of the overall gold production, the numbers may not tell the entire story. In the same report, statistics detailed the level of inaccuracy regarding the reported figures of ASGM.

The numbers show the wide disparity in the quality of the data reported, which is further explained by some countries who are known to export mercury, but do not necessarily disclose all instances of its export, “Trade between the countries mostly appears to be undocumented. For example, Kenya did not register any exports during 2010-15 period.”

While the convention brings more than 100 countries together to address the issue of mercury use, the convention may face challenges regionally in Africa. ASGM is a source of income for many rural families. Taking a hard stance against ASGM, where mercury is the primary agent for ore separation, could hurt a source of income for rural gold miners.

Beyond the individual considerations, country-level considerations are also relevant. Some of the more wealthier African countries play a role in the mercury trade, “Kenya and South Africa were the main supply hubs for mercury used in ASGM, especially in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa itself.” Many of the countries rely on gold production as an important source of revenue. Limiting the use and trade of mercury could have an impact on the gold industries in those countries.

The requirements of the convention also call for swift and decisive action for compliance purposes,

“The convention comes with a long checklist of deadlines. Nations must immediately give up building new mercury mines and, within three years, they need to submit a plan of action to come to grips with small-time gold miners. By 2018, they need to have phased out using mercury in the production of acetaldehyde – the process that poisoned Minamata is still in use. By 2020, they need to have begun phasing out products that contain mercury.”

Three years to comply could pose some challenges to countries who have to not only begin phasing out the use of mercury, but also replace the lost revenue streams from ASGM with new ones.

For more information, please see:

Human Rights Watch — ‘Mercury Rising: Gold Mining’s Toxic Side Effect’ — 27 September 2017

Daily Nation — ‘UN pledges to curb sale and use of mercury’ — 25 September 2017

Phys.org — ‘Something in the water—life after mercury poisoning’ — 26 September 2017

UN Environment — ‘Global mercury supply, trade and demand’ — 14 September 2017

AllAfrica — ‘Minamata Convention, Curbing Mercury Use, Is Now Legally Binding’ — 16 August, 2017