A Gulfstream jet from a quiet airport south-east of Raleigh flew captives to be tortured around the world. The government failed to act but local people have refused to let the issue die

Ayear after he was released from captivity in Guantánamo, Binyam Mohamed received a letter from Christina Cowger, an agricultural researcher from North Carolina. Enclosed was a petition of apology signed by nearly 800 visitors to the North Carolina State Fair.

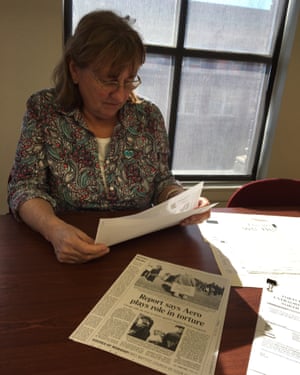

It was “a small gesture”, Cowger acknowledged, but her 2010 letter came with a commitment. North Carolina Stop Torture Now, an organization she co-founded, had been conducting protests, petition drives and legislative campaigns seeking an official investigation into an obscure firm operating flights out of her local airport.

The firm, Aero Contractors, was the CIA front company that operated the Gulfstream business jet that delivered Mohamed to a secret prison in Morocco to be tortured.

Though few government officials supported such an investigation, she wrote, the group pledged “to work toward true transparency and accountability in the United States for the crimes against you and other survivors”.

Seven years later, Cowger sat in the front row of a makeshift hearing room in the Raleigh Convention Center as 11 volunteer commissioners of the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture “upped the ante”, as she put it, on that pledge.

Over the course of two days, this “citizen-led truth seeking commission” called 20 witnesses to testify on the damage done by Aero’s rendition operations.

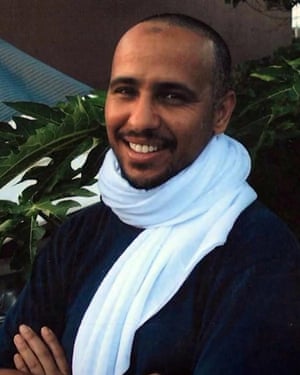

One of those witnesses was Mohamedou Ould Slahi, whose Guantánamo Diaryopens as he is stripped, made to wear a diaper, and shackled aboard Aero’s Gulfstream in Amman, Jordan, in July 2002.

Appearing by Skype from his home country of Mauritania, Slahi faced questions from a panel that included a former chief prosecutor of the international war crimes tribunal, a multi-tour veteran of the Iraq and Afghan wars, a Baptist minister, and a local social worker.

How, the commissioners asked, can we advance an accountability process our elected officials have shunned?

It is a question that North Carolinians have wrestled with before. In 1979, Ku Klux Klan and American Nazi party members opened fire at an anti-Klan rally in Greensboro, leaving five dead. State and federal trials ended in acquittals, and a civil lawsuit raised more questions than it answered about the actions of city officials and police during the event.

Now the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture aims to find a way forward from one of 21st-century America’s darkest episodes – the global operation to seize, interrogate and torture terrorism suspects that Aero Contractors facilitated from the Johnston County airport, a rustic, single runway airstrip 30 miles south-east of Raleigh.

Allyson Caison, a local realtor, first heard the CIA was running “a secret little operation” out of the airport around a Boy Scout campfire in 1996. The subject came up again in the early 2000s, when a relative who was a recreational pilot landed at the airport and marveled at its state-of-the-art runway.

She didn’t know that the “little operation” a former Air America pilot set up years ago in a nondescript blue hangar tucked into the pines employed more than 120 people, or that the Gulfstream jet she would hear taking off and landing was one of the most prolific spiders in what the Council of Europe has called a “web spun across the world” by the CIA’s rendition, detention and interrogation operations.

In April 2005, the New York Times ran a story titled “CIA Expanding Terror Battle Under Guise of Charter Flights” that lifted the lid on Aero’s rendition flights. Later that year, 40 peace activists from St Louis joined Christina Cowger and other local residents to protest against the company’s role in the CIA’s torture program.

“It turned out I knew two of the three Aero principals well,” Caison said during a tour around the airport the day before the commission’s hearings convened. “These were prominent, well-respected business people in our community. Their children and mine were schoolmates. I baked their gingerbread houses for Christmas.”

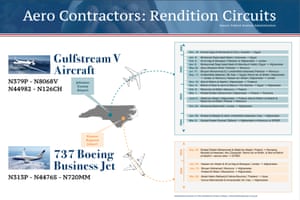

From 2001 to 2004 Aero’s Gulfstream, operated under the tail number N379P, and a second, larger Boeing 737 Aero stationed at Kinston regional jetport in nearby Lenoir County, carried out scores of rendition missions. Together, they accounted for roughly 80% of all the CIA renditions during those years, landing more than 800 times in countries throughout Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Gulfstream was in and out of Guantánamo so often it earned the nickname the Guantánamo Express.

To drive with Caison around the airport is to get a sense of how much nerve this kind of neighbor-to-neighbor activism takes. In the gleaming new Johnston County airport terminal, the young airport manager greeted her with a wary handshake and a gently drawled apology that he could not attend the commission’s hearings.

Down the road, at the recently fortified automatic gate that blocks the access road to Aero’s hangar, there was no pretense of hospitality. It was lunch hour, and a line of cars was filing out the gate. Each slowed at the sight of Caison’s car. One driver, glaring, almost clipped her side view mirror as he inched past.

Caison said: “I really think we’ve changed some hearts and minds around here. People are quiet about it because of Aero’s long tentacles. But we’ve been persistent. It’s the strength of our little group. We’ve accomplished a lot.”

North Carolina Stop Torture Now has had an impact over the last 10 years. Recently released minutes of a closed 2007 meeting of the airport authority in Kinston, where Aero housed its larger 737 rendition jet, confirmed that Aero sold its hangar at the facility that year. When a member of the airport’s board asked its executive director why the company was leaving, the director “explained that Aero Contractors had not had the aircraft in the hangar for several months due to the negative publicity they were getting from Stop Torture Now”.

The campaign scored successes at state level and in Washington too. In Raleigh, the group pressed the governor and state attorney general to open a criminal investigation into Aero’s rendition operations. Told that the state had no jurisdiction, the group drew on a growing network of support from churches to press for legislation to make participating in CIA kidnappings, enforced disappearances and torture state crimes.

The bill twice stalled in committee, but attracted 12 bipartisan co-sponsors and brought the question of rendition for torture before religious congregations throughout the state.

Pressure is also credited with helping persuade Senator Richard Burr, then the ranking Republican on the Senate intelligence committee, to join in voting to declassify the executive summary of the Senate’s scathing report on the CIA torture program in 2014.

Although that report only examined the treatment of prisoners inside the CIA’s black sites around the world, its release sparked hopes for greater accountability over the rendition to bring suspects to interrogation.

Burr, now chair of the Senate’s intelligence committee, has made clear there will be no further official reckoning for the agency’s post-9/11 human rights violations, and has sought to recall and destroy all copies of the still-classified Senate report.

For the volunteer commissioners of the North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torture, this is where their responsibility begins.

“With no meaningful accountability from government leaders, it’s been left to citizens to keep this issue alive,” commission co-chair Jennifer Daskal, a law professor at American University, explained in a break in the hearings.

“We don’t have the power to prosecute, but we can offer an accounting of what happened, and of the costs, to prevent this from happening again.”

“I believe in accountability. I’ve done accountability,” said David Crane, who served as the founding chief prosecutor of the international tribunal that prosecuted Liberian president Charles Taylor for war crimes and who lives in North Carolina’s Great Smoky Mountains.

“Torture is a clearcut issue: you don’t torture. The American people just need to know the raw facts, and many of those facts are right here in North Carolina.”

The commission invited Aero Contractors to give testimony at the hearings, but received no response. Invitations to the governor, attorney general and several Johnston County officials to attend or send representative to the hearings also went unanswered. Calls to the county manager and county commissioners seeking comment on the hearings and Aero’s operations were not returned.

The North Carolina Commission of Inquiry on Torturewill collect evidence through the spring, pressing for the release of public records from county and state officials and compiling research and testimony on the lasting harms inflicted by Aero’s rendition flights. It plans to release its final report this summer.

But the commission’s hearings also sharpened their sense of personal responsibility to repair the harm they see caused by Aero’s operations.

“As a person of faith, I have to be involved in this,” Caison told the commission near the end of the hearing. “As a mom of two boys, I like to think that if my boys were kidnapped, renditioned and tortured, there would be another mom out there at the other end like me, trying to end an injustice that starts in her neighborhood.”

For Cowger, the priority now is to address the physical and psychological health of those who survived Aero’s rendition flights – a process that involves “acknowledgement, genuine apology, and some form of redress”.

“The commission demonstrates by its very being that we are not helpless,” she said.