By: Paola Andrea Suárez Luján

Impunity Watch Staff Writer

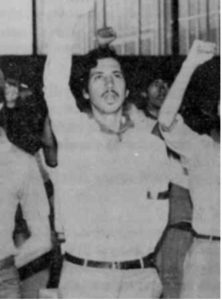

BOGOTÁ, Columbia – It has been 39 years since the imprisonment and murder of Luis Fernando Lalinde, a young college student from Colombia and member of the Communist Party. He was detained without due process on October 3rd, 1984, tortured, and executed by members of the Colombian military. In November 2023, his family petitioned the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to recognize the human rights violations committed by the Columbian state.

|

The truth of the circumstances of his death was the life search of his mother Fabiola Lalinde, who spearheaded Operation Siriri, a search campaign for the truth of his disappearance that lasted more than 30 years. Fabiola Lalinde’s efforts come to life in the hundreds of handwritten notebooks, family photos, and more than 1200 documents recording all information regarding the disappearance of his son. Almost four decades after his death, Luis Fernando Lalinde’s family continues their search for the truth.

In 1988, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights adopted Resolution 24/87, declaring the Colombian State responsible for the detention, torture, and extra-judicial murder of Luis Fernando Lalinde. They urged Colombian authorities to investigate and find the people responsible for his murder. However, it was not until 1992 that Lalinde’s family was presented with his remains, and it was in 1996, exactly 4,428 days after his disappearance, when American scientists confirmed with 99.999% certainty that those remains belonged to Luis Fernando Lalinde. The identity of the perpetrators of his detention and extra-judicial execution, however, remains unknown to the Lalinde family.

For the lack of action from the Colombian government, in 1999 the Colombian Commission of Jurists requested the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights to declare the State responsible for the harm to the psychological and moral integrity of Lalinde’s family members. They alleged that the State deliberately obstructed Lalinde’s family’s access to adequate remedies for the investigation and punishment of those responsible for his detention and execution, depriving them of their right to obtain justice.

Lalinde’s case investigation was performed mainly under military criminal jurisdiction. The Commission stated in its Merits Report No. 292/21 that, by leaving the investigation to military jurisdiction, the Colombian State violated judicial guarantees and protections. There was no independent and impartial authority in the case that could allow for a fair investigation and adequate sanction of the people responsible for the acts committed against Luis Fernando Lalinde.

Following that petition, the Colombian Commission of Jurists, representing Luis Fernando Lalinde’s family members and following his mother’s lifelong mission, has requested the Inter-American Court on Human Rights on November 6th of this year, on behalf of the Commission, to declare the Colombian State responsible for the violation of the right to personal integrity, judicial guarantees and judicial protection in detriment to Fabiola Lalinde, Jorge Iván Lalinde, Mauricio Lalinde, and Adriana Lalinde.

Lalinde’s family is requesting that the Court order the Colombian State to fully redress the human rights violations committed against them and that measures be adopted so they can receive comprehensive medical care. Following a 40-year-long plea, they also ask that the Colombian government conduct and conclude an impartial and effective judicial investigation to establish the circumstances of the disappearance and death of Luis Fernando Lalinde, as well as identify and sanction all individuals involved in the events.

The ongoing fight for truth by the Lalinde family is accompanied by the families of more than 60,000 disappeared individuals in Colombia in the last 45 years. The request to the Court calls for an analysis of the impact of the prolonged impunity of serious human rights violations on the personal integrity of the victim’s families.

For further information, please see:

IACHR – Petition Before the Inter-American Court Of Human Rights Case 12,362 – 6 Nov. 2023

CCJ – Luis Fernando Lalinde was Disappeared 37 Years Ago by Military Forces – 3 Oct. 2021

El Colombiano – The Long Flight of the Ciriri, the History of Fabiola Lalinde – 13 May 2022

Cero Setenta – Operation Siriri or How to Find a Missing Child – 30 Apr. 2018

UNAL – Data base: The Fabiola Lalinde and Family Fund – 20 Apr. 2022